Andreas Herm Baumgartner with the chamber orchestra of the Bavarian Philharmonic Orchestra at Wasserburg town hall concert

From: Oberbayerisches Volksblatt (October 27, 2010)

Source (originally in German): http://www.ovb-online.de/kultur/dokument-schwerer-zeit-begeistert-979475.html

The music of Schubert, whose soul sometimes sought ways of expression in which he exploded the possibilities of the four-part instrumentation of a string quartet; Karl Amadeus Hartmann, considered the representative of musical expressionism in the classical modernism of the first half of the 20th century; plus a conductor who dedicates himself with extreme devotion to precisely this type of music: a stroke of luck for Wasserburg’s music lover to be witness to a concert that united such trinity.

The lucky circumstances: the conductor Andreas Herm Baumgartner was born in Wasserburg – and that may have been a driving force for a Wasserburg town hall concert in which the programme went beyond the usual framework. In addition, another ensemble had to cancel, so that the chamber orchestra of the Bavarian Philharmonic, an ensemble mainly of young people, could be won over. And finally Klaus Jörg Schönmetzler had agreed to introduce the program and especially the music of Karl Amadeus Hartmann.

Let us turn to Schubert: his D minor quartet (“Der Tod und das Mädchen”) seems so explosive already in the first bars that the transfer to string orchestra seemed to make sense and emphasized the force of the first chords. This exponentiation of the expression should be confirmed in all subsequent movements. But the part of the first violin, which reaches heavenly heights, is difficult for the string section to perform in complete homogeneity – which is why the conductor did well to entrust some chirping passages to the concertmaster alone. The vulnerability, in addition to orchestral power, is always an indispensable characteristic of Schubert’s music, and thus sounded episodic even in the orchestral version.

Baumgartner worked out the depth of the famous song theme even more intensely than in the quartet version, tracing every imaginable nuance in his conducting, his gestures, and in the Rondo, the ensemble grew beyond itself as it mastered this rapid final movement with unprecedented precision.

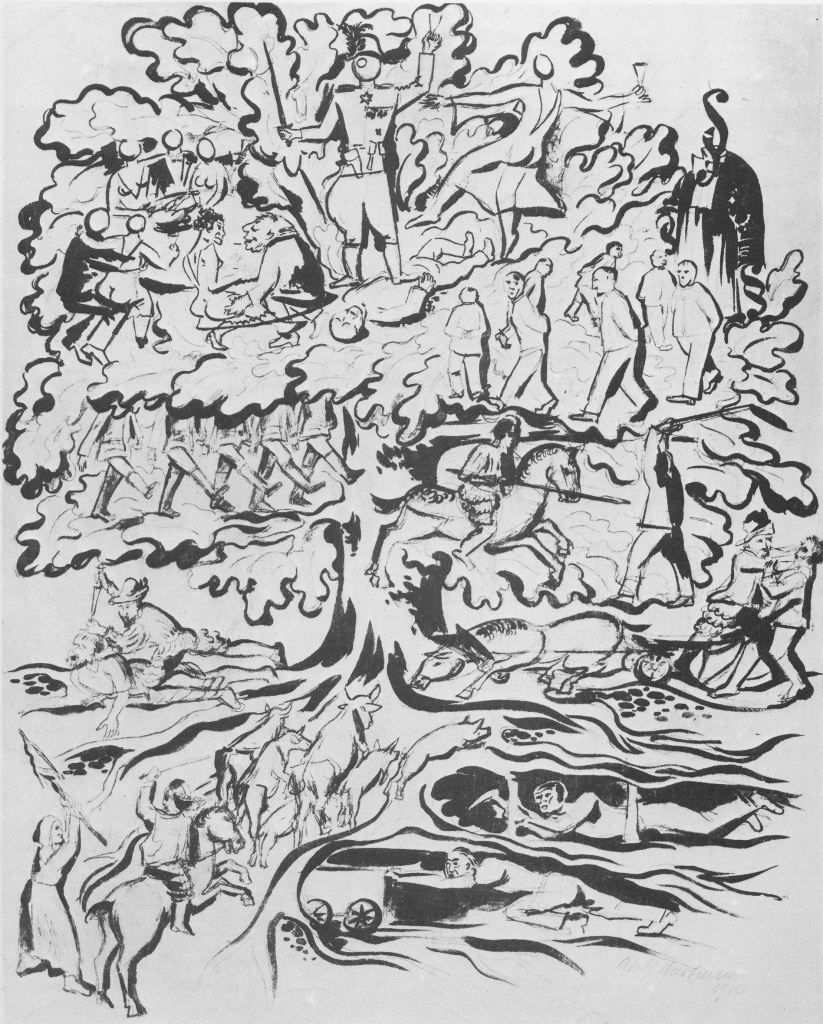

The break now helped to bridge 100 years of music history, the tension in the audicence was clearly noticeable. The expressive play of before culminated in Karl Amadeus Hartmann’s 4th Symphony – begun in 1938, first performed in 1948. Klaus Jörg Schönmetzler had given the listener details of the structure of the work, and the reference to many a 12-tone motif or to Yiddish themes helped the understanding. But what did the composer write about this? “(Das Werk) braucht nicht verstanden werden in seinem Aufbau oder seiner Technik, sondern es soll verstanden werden in seinem Sinngehalt.” [“(The work) does not need be understood in its structure or technique, but it should be understood in its meaning.”] It is probably the vita in bad times of oppression which opens up this meaning – which the speaker talked about in detail.

And so they listened: The unison of the beginning alone is of hardly surpassable intensity and immediately captures the listener. How is this increase still possible? Yes, the overlapping voices increase the expressiveness, the chord clusters rub in the ear.

The second movement, a kind of scherzo, evokes Bruckner or Mahler’s grim humour. Was all this really to be called “atonal”? Unusual, yes, and one would have liked to hear the last movement a second time, because its conclusion posed a riddle that everyone, even the connoisseurs, may well accept as such: The cellos indulge in the solo, almost bursting with intensity, nothing more is possible. A final note. Desition. Silence, from which stormy applause grew.

A testimony from a difficult time became tangible, and if the younger generation was as enthusiastic about it here as it was in the post-war years, the older generation may be particularly pleased!